How to help a student get unstuck

When I was eight years old, I had a profound realization: once you know how to read, it’s impossible not to. If you see the letters c-h-a-i-r in sequence, your mind conjures sit-able 4-legged furniture. You don’t choose to read or not read, you just do it. And it’s impossible to understand what it’s like not to be able to read.

The same principle applies when learning how to code. Once you understand how it works, it’s extremely challenging to imagine not understanding it. This can be problematic when teaching because it creates a gap between teacher and student. Even the most empathetic teachers can’t quite imagine themselves in a student’s shoes[1].

Getting a student from naivety to mastery takes a lot of work from the student and the teacher. But the work is asymmetrical. As a teacher, your role is to accompany, you can’t walk the student’s path for them. All you can do is support them through the journey as best you can.

This article is intended to share some techniques I’ve developed for teaching debugging in a one-on-one setting. If you find this useful, let me know, and I’ll write another one about helping students who are pair programming. I wrote a follow up article discussing dynamics in pair programming.

Forget about the program, focus on the programmer

Most programmers enjoy programming, and love solving a good problem. When you’re helping a student write a program, you have to fight the urge to fix the problem. Forget the program is even there. You may just want hop through a few files and figure out what’s going on. Stop. Fight that urge.

While it can be marginally helpful for a student to see you at work, it’s not nearly as useful as it would be to help them solve the problem. You’re not there to get the code to work—that would be consulting. You’re there to get the programmer to work.

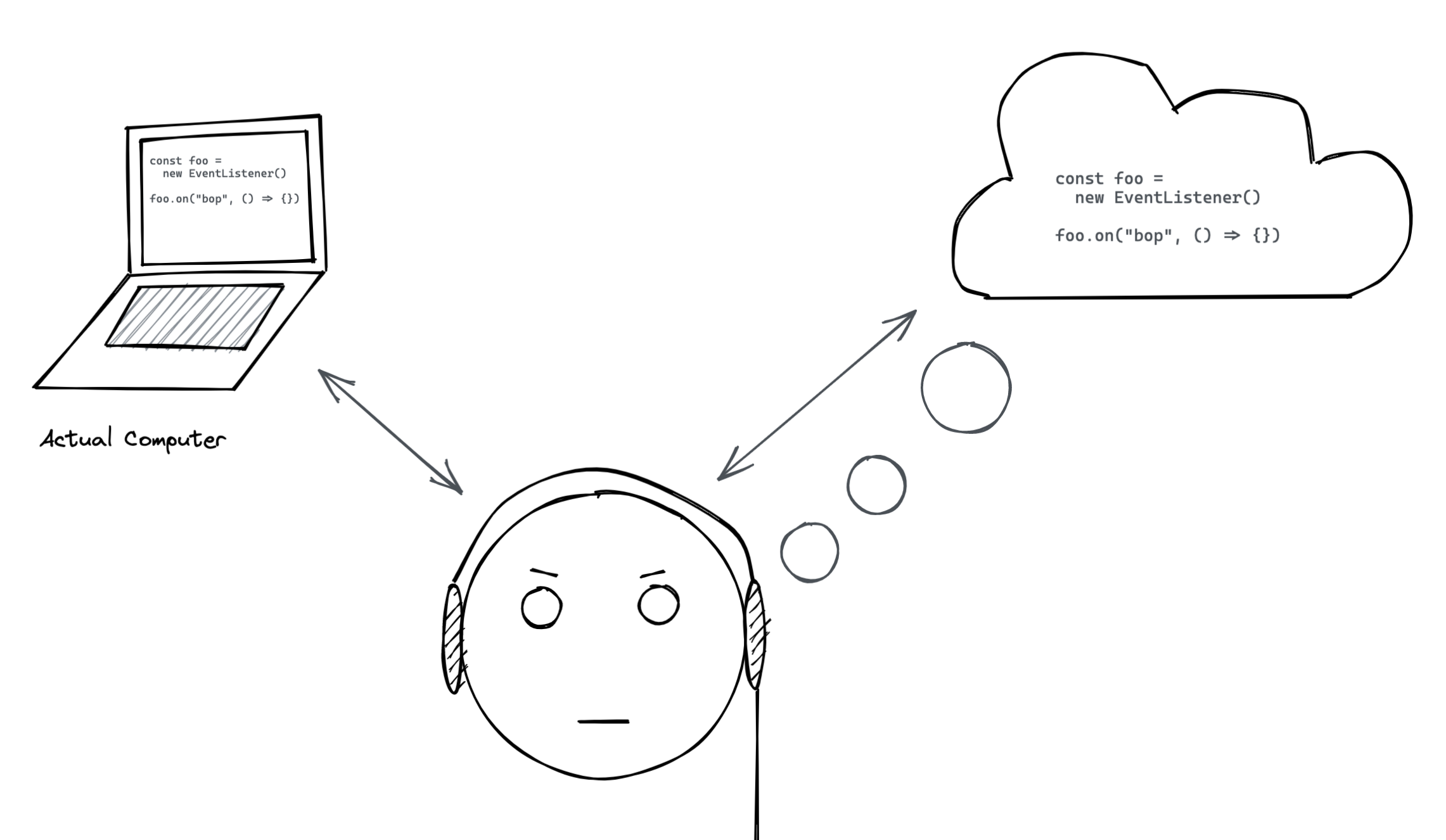

As programmers we construct an abstract mental model of the program we’re writing. Bugs are discrepancies between our mental model of the program and the program itself. The program is doing something we don’t expect. The program isn’t wrong. The program can’t be wrong. It’s doing what it’s been told to do. What’s incorrect is our mental model. Once we understand the current state of the program, we can adjust it.

The art of debugging is systematically and creatively synchronizing the mental model with the actual program.

As you teach, your focus should be on the student’s ability to keep the two in sync, not your own.

Don’t let them overheat

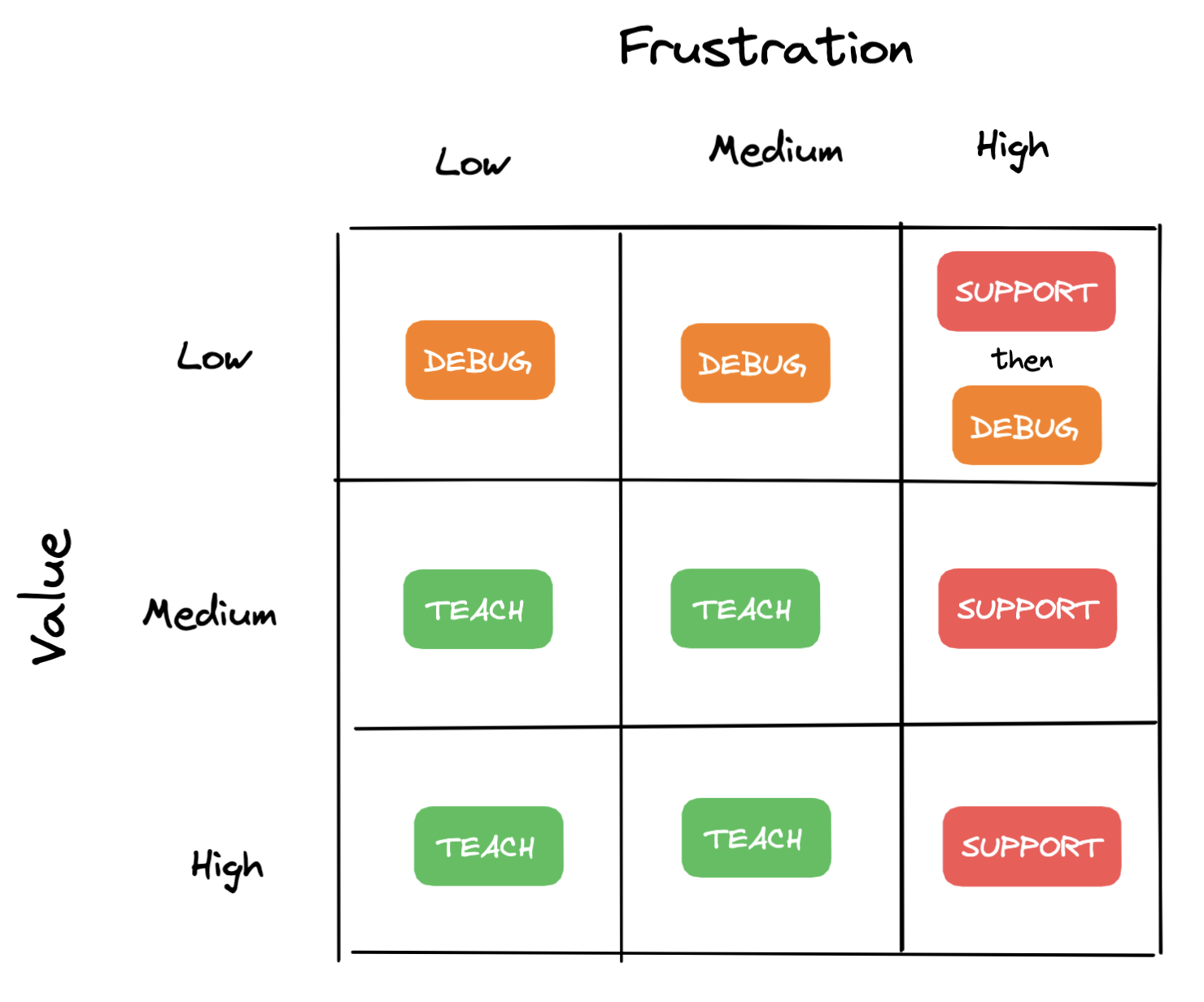

Debugging can be frustrating. Every programmer knows the difference between productive friction and wheel-spinning. Your student can’t always tell the two apart. It’s your job to keep an eye on their frustration level, and adjust your support strategy accordingly.

Consider both the frustration level of the student and the instructional value the moment offers.

If they’re getting stuck on some tiny little problem, and the answer’s starring them right in the face, just fix it for them. It’s not worth pulling out the socratic method to fix a missing comma.

If they’re profoundly frustrated, even if the moment offers tremendous instructional potential, hit pause. Take care of the human being in front of you. The programming concepts can come later.

Depending on the level of trust you’ve built up with the student, you may be able to teach through more frustration than you would with a brand new student.

So, You’ve identified a strategy. But how do you teach, how do you support and how do you debug?

How to teach

Try to ask questions more often than you give information. It’s totally fine if you tell students things here and there, but try to lead them to answers whenever possible. I’ve found that sometimes I can deliberately slow down my own thought processes, and shield myself from what I think is the right answer. By doing this, I’m able to pose questions that I don’t know the answer to (“I wonder what the state of the user record is right now?”).

If you’re teaching in-person, avoid touching a student’s keyboard. When I was new to teaching, I would sit on my hands so I wouldn’t be tempted to take over. If you need to show an example of something, use your own computer.

Offer lots of encouragement. Every idea is a good idea. If they’re at risk of rabbit-holing, gently coax them out of it with a question, observation, or suggestion, for example, “that’s a great thought… I don’t think we’re going to find the answer there… tell me, do you think this code ever runs? I’m starting to wonder if the problem is upstream.”

When you get a sense of closure on a topic, prompt the student to summarize what they’ve learned. Finding the right time to summarize isn’t totally cut and dry, but I’ll offer two metaphors. When the “mental callstack” is empty, summarize. When get that feeling like “I should make a git commit,” summarize. Students sometimes get overwhelmed by the details, and if they never take a step back and appreciate the forest, all they’ll remember are trees.

How to debug

So, you’ve decided that the best course of action is to take over and solve a student’s problem for them. The way you do it matters. You want to make sure you’re honoring the weight of the problem. They’re not stupid for not getting it. Show them that even professional programers get stuck, and that there’s a methodology for getting unstuck.

It’s important that they can follow along. You might be making certain observations--voice them, and then check to see that they’re with you (“oh, it can’t be a problem in the checkout service because we haven’t even passed validation, yet… do you agree?”). Make lots of diagrams.

Practice good hygiene. Even if you might throw a bunch of random logs all over the place when you’re coding alone, try to demonstrate best practices. You don’t want to model your own bad habits.

When it’s fixed, go over everything again. Talk about what the problem was, how we figured it out, and how we fixed it. Once you’ve done that, check and make sure they’ve got it.

How to support

Some moments are “teachable” and some aren’t. Learning to code is hard, and you will find students who are so frustrated or anxious that they can’t learn. This isn’t the time to pivot to your favorite debugging technique. Instead, be there for them. Hear their concerns and anxieties, and let them know that they’ll get through it.

If you’re in a setting around other students, take them aside. It can be hard to have a vulnerable conversation in public. Maybe take a walk or go into another room.

The most important thing you can do is listen. Ask them what’s bothering them. Make sure they know that you heard them by repeating it back in your own words. If you don’t have it right, keep working at it until you do.

Lots of early stage programmers don’t realize that it’s normal to struggle. They may not be aware that you had analogous struggles. While this isn’t about you—it’s about them—it can be helpful to tell them about the ways you struggled while you were learning, and the ways you struggle today.

It can be hard for students to grasp the progress they’re making when they’re in a rut. At times, I’ve pulled up prior work from the student and emphasized the growth they’re making. “I know how frustrating this is. I just want you to know that you’re growing, and I see that. See this? You wrote this two months ago. I bet you’d do it totally differently today. What about this? You did this last week, you couldn’t do that two months ago.”

Taking a break is almost always necessary before diving back into the IDE.

Putting it all together

You can mix and match these techniques. You can throw some out and add your own. It doesn’t have to be 100% one and 0% the others. You’re not a machine. Every teacher and every student is different. The art of teaching is finding a technique that works for the situation at hand.

Can’t tell if it’s working? Ask your students. “When we took a walk and talked through things, was that helpful?” “When I ask you all these questions as you’re coding, do you find that useful? I sensed some frustration.” Just like you can’t know the state of an application without a breakpoint or log statement, you can’t know the state of your students without talking to them. What they say may surprise you, and it’s important for fine tuning your craft.

@Ozzie_osman on hackernews told me that there's a formal term for this: The Curse of Knowledge ↩︎

- Next: Zeke's new brand rollout

- Previous: Cost of computing