Helping students with pair programming

I wrote an article about how to help a programming student get unstuck, in it, I offered to share my thoughts about how to help pairs of students get unstuck, and this is that article. If you haven't read the original, I'd suggest starting there, because many of the techniques that work on individuals also work on students who are pair programming.

What is pair programming

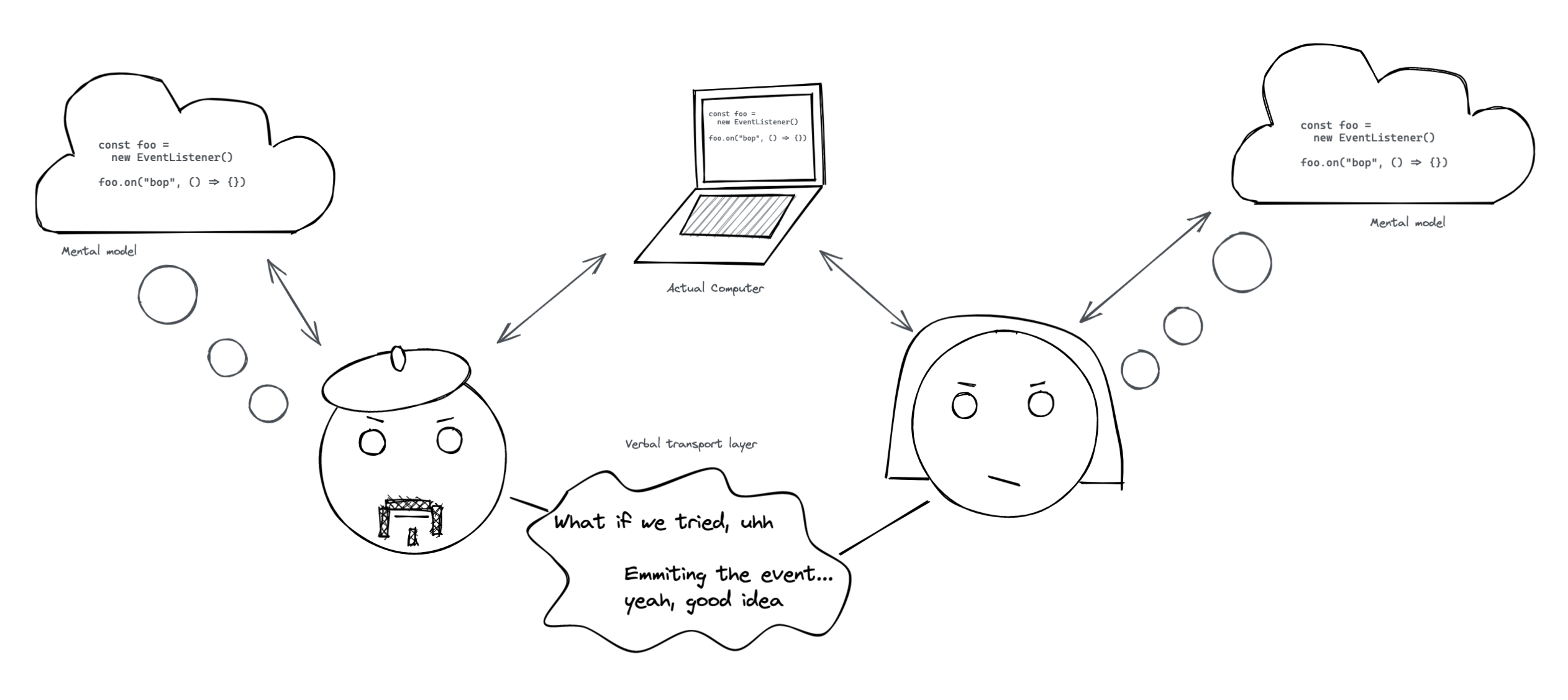

For the purposes of this post, I'm going to define pair programming somewhat narrowly. It's when two programmers are working on one computer, in collaboration, to write a program. When people pair, there are three versions of the program running--one on the computer, and two more in the minds of the programmers. If you've ever worked with distributed systems, you know that adding nodes generally makes things more complex, and this is no exception.

When individuals are debugging code, they need to synchronize their mental model of the code with the actual program on the computer. When you pair, you have to sync your mental model with the program and the mental model of another human being. In order to do that, you have to do a lot of talking. I find pair programming to be profoundly rewarding, but also fatiguing for this reason.

Does it work? Is it good for students?

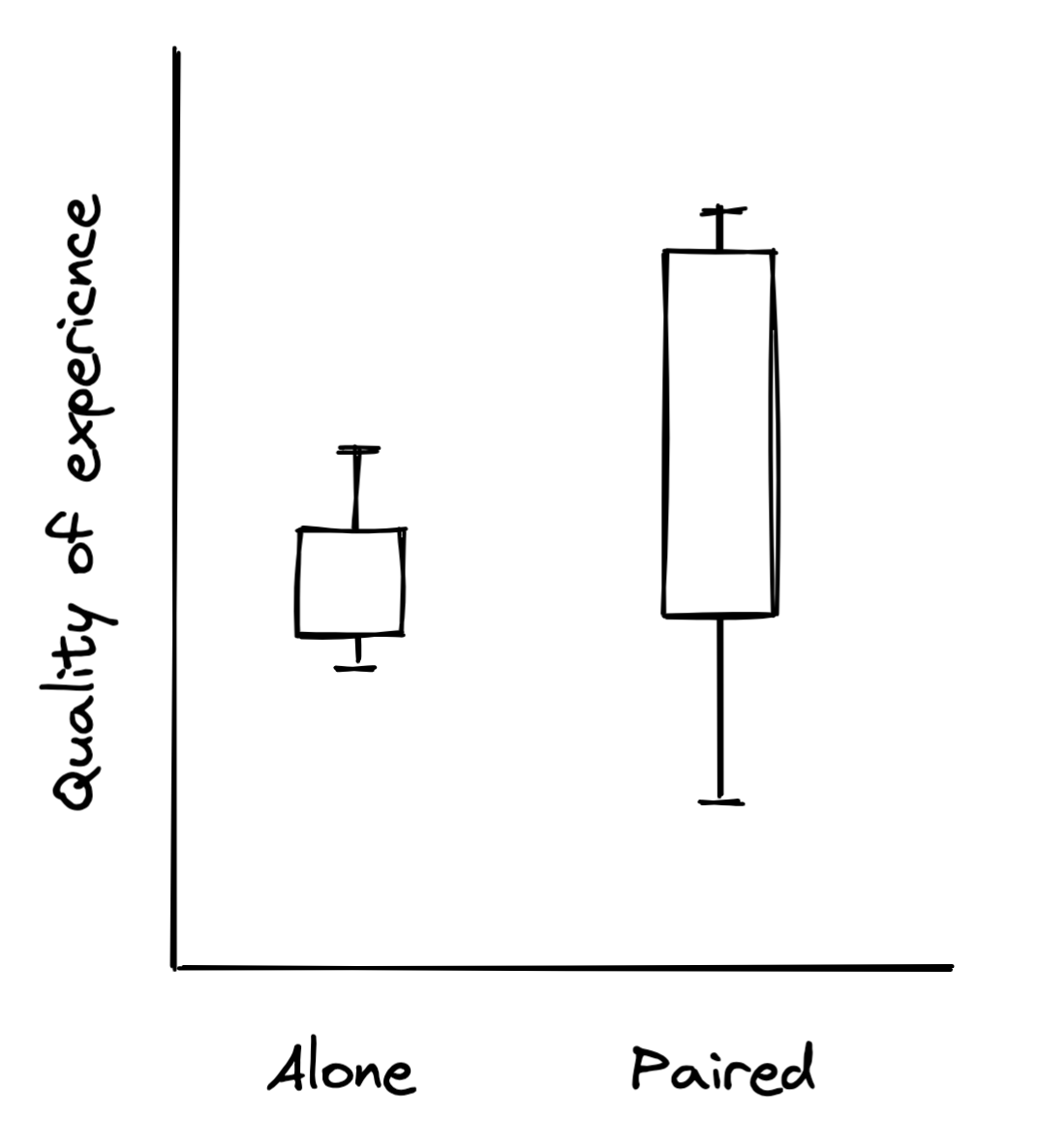

Pair programming may not be for everyone. Even if you like it, you may not love pairing with everyone. As in all human affairs, personalities and styles sometimes clash.

By and large, code written by pairs is better than code written by an individual because it forces you to understand how your code will be read. Of course the code you just wrote makes sense to you--you just spent hours mind-melding with a computer. To make it run smoothly in someone else's brain, you have to also mind-meld with them.

But what about pair programming for students, specifically? There's a wide range of experiences. The average student will learn more, and have a better experience pair-programming than writing code alone. They learn how to talk about their work--which is hard to teach, they find bugs themselves as they talk through their program, and they keep each other motivated when the going gets rough.

When things go wrong

When students are pair-programming, it can go sideways for countless reasons. Sometimes it's fixable, sometimes it's not. Here are some of the causes of bad pairing experiences.

- Confidence mismatch. There's a surprisingly weak relationship between competence and confidence in early programmers (and beyond?). Sometimes a pair have similar understanding of the material, and similar capabilities, but one party will have far more conviction about their ideas. This can exacerbate imposter syndrome, and lead to other problems.

- Incompatible coping strategies. Student A needs a break and student B needs to dig in. Student A wants to ask for help, student B isn't ready to give up. Student A wants to know that it's OK if they don't finish the exercise, and student B believes that thinking about failure brings it on.

- Misplaced authority. As you observe them work, you notice that one person takes on the role of an authority figure. Sometimes, a student will pull up the wrong social template, and act with authority, greatly limiting the partnership. It's possible for this social template to come from either or both individuals. That is to say that sometimes someone is accustomed to working for someone rather than with them.

- Communication crunch. Take two normally good communicators, and then ask them to have a tactful conversation when they both really need to use the bathroom, and are changing lanes on the highway... they will no longer be good communicators. A similar phenomenon can happen with pair programming. You may find that some people unconsciously become tone deaf, inarticulate, and short tempered. This may or may not happen to everyone, and the severity varies. The effect tends to be proportional to mental strain, so as students become more comfortable with the material, this is less of a problem.

- Bad vibes. This is something of a catch-all. These two individuals just don't get along. They keep misreading each other's language.

How do you know if something isn't working? Often it's quite obvious, but it can be more subtle, at least early on. Here are some of the signs of a problem.

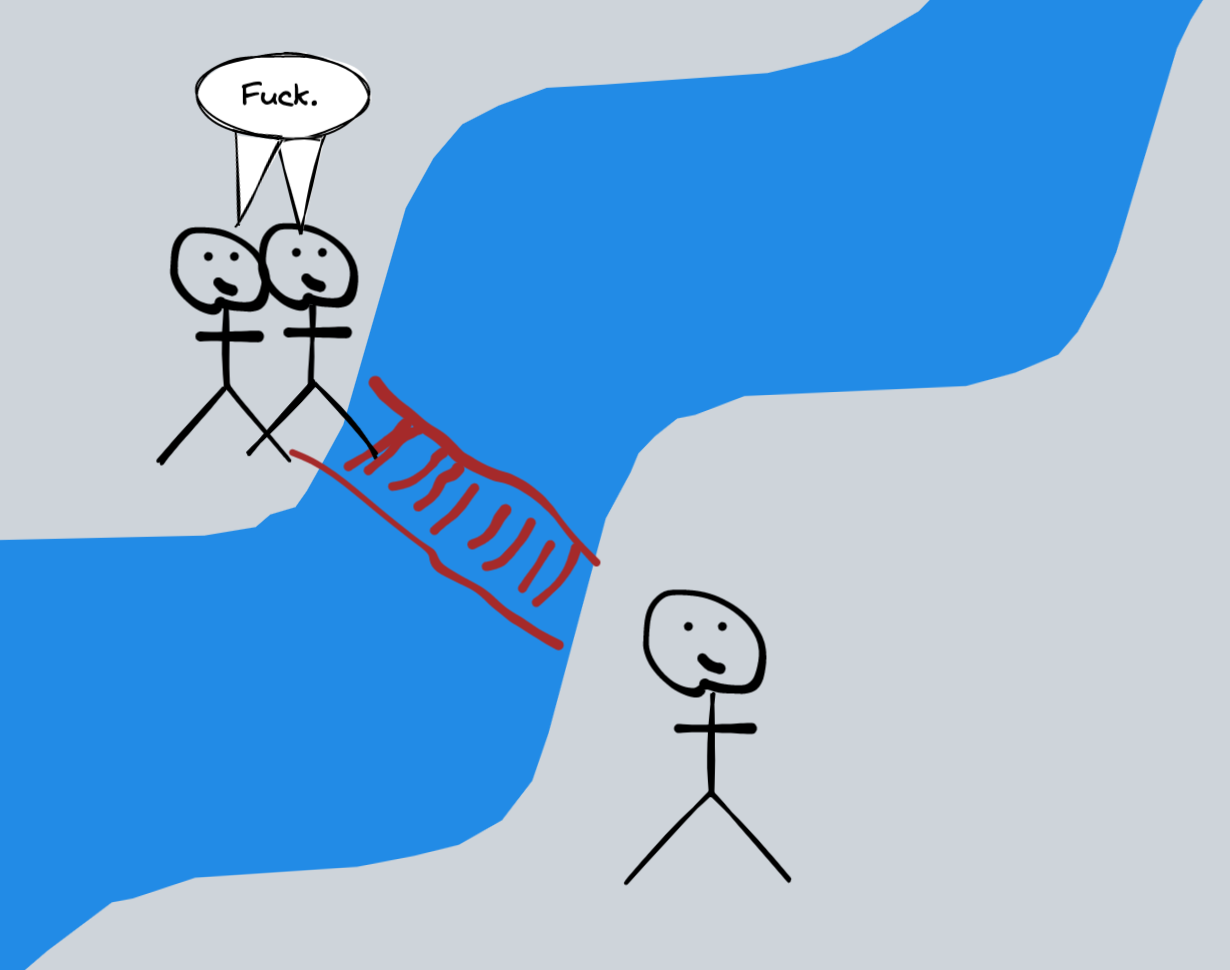

- Not pairing. Two computers, little dialog. This pair isn't pairing, they're collaborating on separate threads.

- Signal imbalance. You're called over to help, and you're only hearing from one person. The other person is checked out, or steamrolled, and the person doing the talking is ignoring their partner.

- Command stream. You overhear students working and their dialog sounds more like a stream of commands than a two-way collaboration. "now type new function... no parentheses here, I like to have arrow functions." A healthy pair will generally be bouncing ideas, questions, and encouragement back and forth.

- Frustration meltdown. Sometimes things will get so bad that there's open hostility between students. This can happen for many reasons, but it's pretty hard to miss when it happens. It sounds like people fighting.

These problems show up in classrooms, but they're not exclusive to them. I haven't been teaching in 5 years, and I see these kinds of problems all the time amongst coworkers. And just because I understand them, it doesn't mean that I'm immune. Sometimes I even know what's happening but can't quite fix it.

Preventing problems

There's no way to prevent 100% of pairing problems. But, there are some things you can do from day 1 in a classroom to minimize them.

- Set expectations & norms. A lot of frustration comes from mismanagement of expectations. Tell students to expect some friction. Tell them what is expected of them when it comes. Provide ground rules for how students are expected to treat each other.

- Give them tips ahead of time. "If you're having a hard time getting your point across, try a diagram. If that doesn't work, try to ask your partner to say it back in their own words." "if you have a disagreement about direction..."

- Tell them why students do pair programming. It's valuable, and there's a reason why you decided to set up your class in a certain way. They'll be more bought in once they understand that.

- Adjust pairs. Over the course of the term/semester/cohort, adjust who pairs with who. You'll get a sense of individual pairs chemistry and have ideas for better matches. Matching isn't all about skill level (I love pairing with programmers of almost all levels, learn a ton every time). Skill level can come into play, but matching on skill level alone will not solve your problems. You could get really data-driven about it, and I've tried, but if your class-size is small enough, you'll learn who fits well with who. You can send our surveys, that's something I've tried with mixed results. If you do that, make sure students know that their partner won't be in trouble if they give a negative rating on the experience.

How to help

When you are called to help a pair, fight the urge to sidestep interpersonal issues. If you observe a dysfunctional dynamic, help the relationship before helping either individual, and certainly before "helping" the computer. If you parachute into a toxic dynamic, tap a few keys, and make an error go away, you're kicking the can down the road[1]. That's not to say you must completely fix the social problem before moving on--that is very likely impossible. But, if you ignore it, tensions will compound, and it will be harder to address later.

Debugging interpersonal issues is tricky, and there are entire professions dedicated to it. There's no formula. If you expect yourself to be able to "fix" it, you're setting yourself up for disappointment. But, you can help, and over time things really can improve.

A good starting point for solving any problem is understanding it. Build your mental model of the social problem. Ask the students what's going on. Name the tension, and see what happens. With no judgement in your voice, try something like, "I'm picking up on some tension... is it fair to say you're both feeling some frustration right now? What's going on?" Then see what happens. If the students are willing to talk about how they feel, make sure to show them that you're hearing them. It's hard to predict where this goes, but sometimes it's cathartic for students to have the issue out in the open.

Depending on the level of tension, you may to take a break before returning to content. "It seems like lunch is in 15 minutes, why don't we break early and come back to this first thing after lunch." Time and nutrition can be as good a medicine as the best diagram or explanation.

When everyone's ready to turn to content, you can act as a communication bridge to address many communication problems. Slow things down. Make sure at every step of the conversation, the two individuals hear each other. Point out for students when you think there's a communication problem. Try bringing in diagrams, rephrasing, examples. You can also inject a different energy into the dynamic with your own reactions, "ooh that's a really interesting question!" Just make sure it's authentic... injecting bullshit into the dynamic probably won't help. In a similar vein, when there's a win, take time to celebrate it.

You can pull back the curtain and explain what you're doing. "I'm trying to improve our communication dynamic because I think a lot of the problems we're having stem from the fact that we're not hearing each other." You can also offer suggestions. "What if you used diagrams like we have over the last 15 minutes."

Throughout this process, you may experience strong feelings. You can get frustrated, too. Keep an eye on this. If you're getting frustrated, it's probably time for a break, a new approach, or to maybe pull in another teacher or TA. It is possible to make things worse.

If nothing works, talk to them one-on-one later. See if they're more open when apart.

Pair programing is fraught with problems, but at the same time, it's 100% worth it in a classroom setting. Students learn more about code, more about their own communication dynamics, and are more resourceful than they would be alone. But, without some hands on social support, there will be enough failure cases that you might conclude it's not worth it.

These techniques are personal. They may not work for every teacher or student, and that's OK. I hope they serve as fodder for thought and discussion. I'd love to hear from other programming teachers about your experiences with pair programming in the classroom. Has it worked for you? Been a train-wreck? What do you do when students have problems?

I'm sure there are exceptions to this. Perhaps the error itself is adding to the tension, and taking it off the table right away will make it easier to figure out the real issue. Trust your gut. ↩︎