Elevators, Subways, and Rocket Launchers: The Unpredictable Path of Software Development

There's been plenty of ink spilled on the topic of what to call software engineers. Hackers? Coders? Developers? This semantic debate has been mostly boring to me until recently. It's hard to find one term to use to describe our job because our job can change so much from day to day.

When you're building at scale, the job can superficially resemble classical engineering. You need to build a model of the system based on empirical data, understand the constraints of the system, and build with enough flexibility to avoid a range of disasters.

On the other hand, if you're building a new product that has no users, you use a profoundly different toolkit. The product itself is a hypothesis. You're trying to make something useful that doesn't yet exist. There's no reason to believe the thing your building will solve a real problem. You need to figure out how to build something as quickly as possible without contaminating the experiment. If you make it too cheaply the jankyness will get in the way and no one will use it, even if the idea is great. But, if you decide to use Kubernetes and micro-services with mature observability, you'll never stand anything up at all.

I've worked at startups and now I've worked at a couple bigger companies for a few years, too. I've been surprised to learn that you still need "hacking" at large organizations. Some projects–a prototype of an internal tool, for example–call for "hacking" while others that will be trafficked by millions of people need "engineering."

This one dimensional spectrum that I've described with "hacking" on one side and "engineering" on the other is still too simple.

Some days I'm a detective or a spy, trying to understand how someone exploited (or could exploit) a system. How do we know someone is who they say they are? Could anyone sneak past our security? How would we know that they did? What's the worst thing that might happen if they fool us?

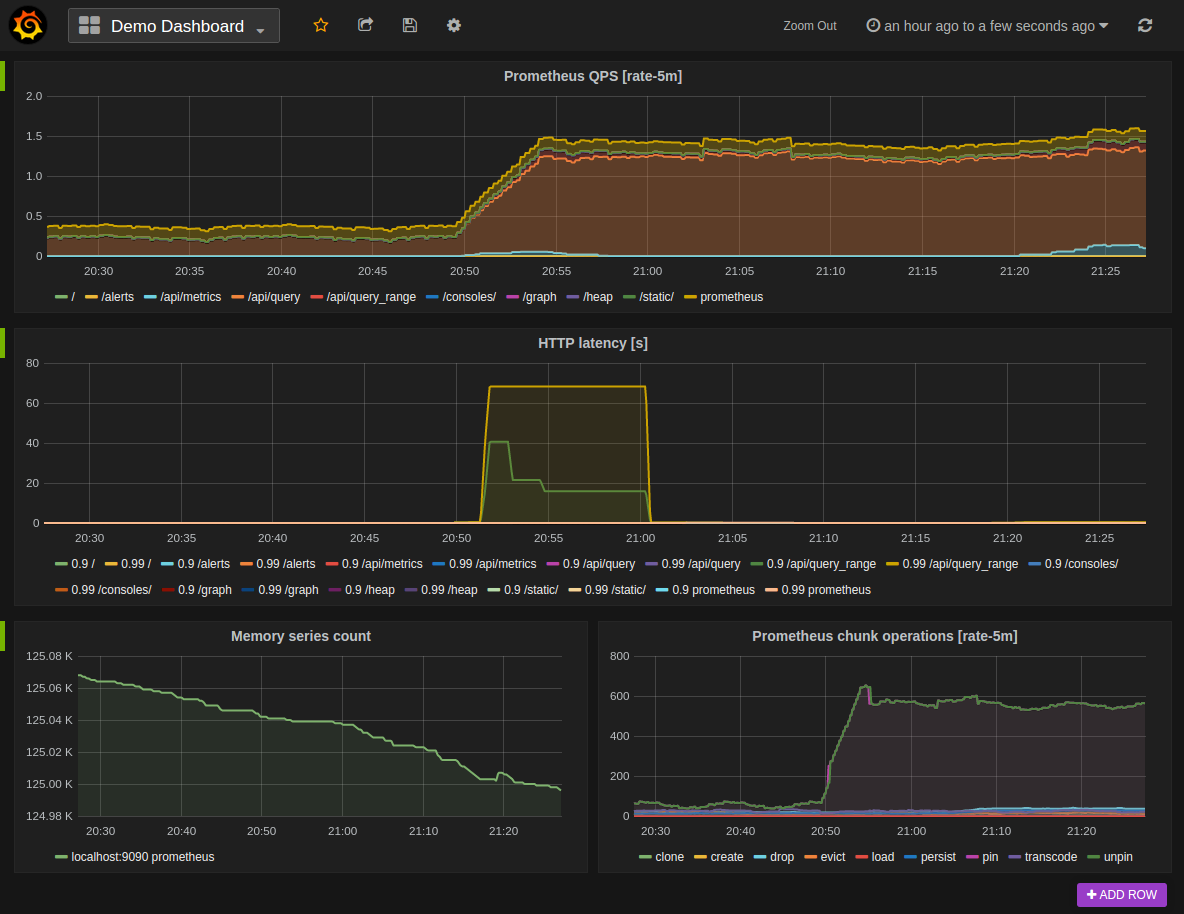

Other times I'm wearing the hat of an ER doctor trying to understand the pathophysiology of the system in distress. "What could cause X reading to be elevated with Y symptom.... who should we page in for a consult? What can we do to stabilize the patient while we work on a diagnosis?"

I've occasionally worked on "core" projects where my goal is to support other engineers in what they build. When I'm doing this I need to consider the emergent properties of a team of hundreds of people, slowly turning over over decades. People don't have perfect visibility or discipline. How can we create incentives for people to do the "right" thing? How can we make it as easy as possible to modernize legacy surfaces. On those days it feels like I'm almost an urban planner, economist or even a politician.

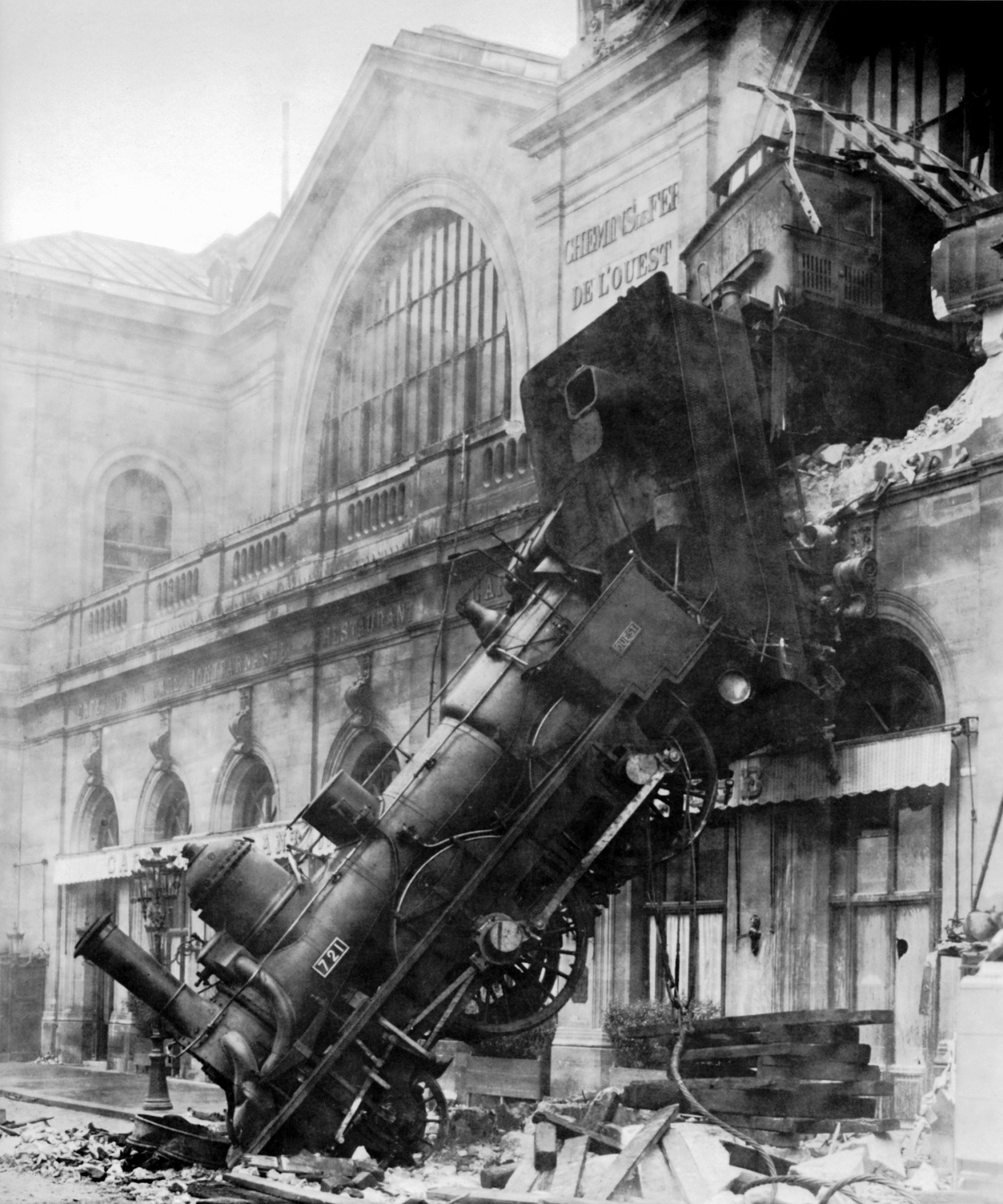

As software engineers, the things we build are unlike anything else out there. They're in constant flux and can change drastically over long periods of time. Imagine if the people building an elevator system in a skyscraper found out a decade later that they were actually building a subway system! That's what it sometimes feels like. The decisions that were made when you were making the elevator don't always hold up in hindsight. The context has shifted 90 degrees.

And yet, you can't start over–a million people are using your subway every day. You just have to move forward with an eye toward the future. For all you know you might need to make this thing into a rocket launcher a decade from now.

If I can leave you with one piece of advice... No one tells you when it's time to switch toolkits, and and it's necessary. If you miss the moment when it's time to change things up, your project will be in trouble. This job requires enormous flexibility. Ask yourself and your team, "what tools do we need for this project?" or "is it time to switch hats now that this thing is out in prod?" There's a lot to learn from different disciplines and from each other and we're still at the beginning.